Little's Law Doesn't Work

Little’s Law is well known, but not well understood. Daniel Vacanti has some deep insights into the assumptions that need to be made to make Little’s law “work” for you.

I remember being mesmerized watching one of my favorite humans, Steven Borg, talk about flow in knowledge work. Watching him train teams on queues and lean practices was amazing. Of course, Steve pointed me to The Principles of Product Development Flow by Donald G. Reinertsen and I highly recommend that you read it if you’re in any kind of knowledge work.

It’s been a while since I read anything fresh on these topics - mostly due to a change in role for me at work. I’m doing more technical sales than delivery, so I don’t get as much time code-slinging and working with teams as I used to. However, I finally decided to read some work on Agile metrics by Daniel S. Vacanti.

Daniel makes application of some of the math and statistics of agile metrics easy to understand and absorb. I’ve been thinking a lot about his writing, and I wanted to jot down a few of my thoughts.

Little’s Law

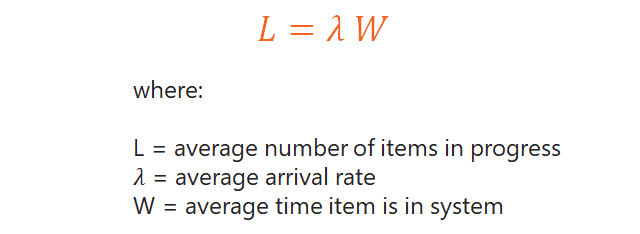

If you’ve ever seen any Lean talks or materials at all, you’ll undoubtedly have come across Little’s Law. Little’s Law originally is written as follows:

This is written in terms of arrival rate.

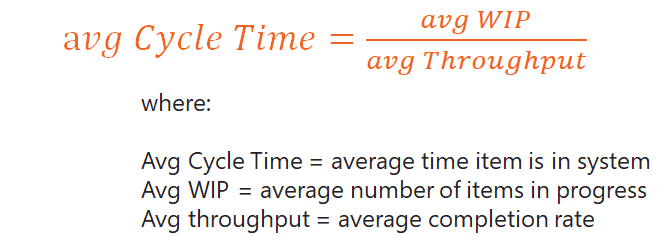

In knowledge work, you will more commonly see it written as:

This is written in terms of throughput or completion rate. This was something I had never considered before and Vacanti goes into detail about why this is an important distinction. In short, there are a couple of assumptions that need to be made to make the law work - if you don’t adhere to these assumptions, then the math breaks.

The other epiphany I had was that Little’s Law should never be used for forecasting - I’ve always heard Little’s Law bandied as a method to apply some easy math to predict forward what cycle time or throughput is going to be. Vacanti says that at best it can be used to do a gut-check, but should not be used to provide estimates.

The question is then: is Little’s Law a lie?

Assumptions That Make Little’s Law Work

Vacanti lists five assumptions to make Little’s Law work. The fifth one is really simple - make sure you’re consistent with your units for Cycle Time, Work in Progress (WIP) and Throughput, so no need to go into too much detail on this one.

Let’s take a look at the other four, which really revolve around the stability of the system under observation. The more stable a system is, the more useful Little’s Law will be. (Statisticians speak of how stationary the underlying stochastic processes are - but what that really means is how stable the system is).

1. Average Input Rate Should Roughly Equal Average Output Rate

The original form of Little’s Law is written in terms of arrival rates, while the knowledge work form is written in terms of departure (throughput) rates. So it makes sense that these should be roughly the same for the law to hold. Most teams will notice that work does not exit their processes at the same rate that work enters their processes. If you plotted arrival rates and departure rates over time, you’d see that the arrival rate gradient would be greater than the departure rate gradient - you’ll see this on Cumulative Flow Diagrams (CFDs).

The reason that Little’s Law doesn’t work in this case is that work gets stuck in the system and skews the averages. Remember, the law is written in terms of averages, so large deviations from the averages are going to break the math. More on variability later.

2. Work Started Must Eventually Exit

This should follow naturally if arrival and departure rates are roughly the same. Teams should be relentless in ensuring that work started is completed. If work is hanging around for long (indefinite) periods, it will break the math.

3. WIP Should Be Roughly The Same at the Start and End of the Measured Period

For any time period that you measure, you should have roughly the same amount of WIP at the start and end of the process. If you’re on a (pure) Scrum team, you should always end your sprint with 0 WIP. Technically you start with 0 WIP too and pull in as the Sprint proceeds - but teams that carry WIP from Sprint to Sprint will probably notice that Little’s Law doesn’t work so well for them because they’re breaking this assumption.

If you’ve recently added a lot of work into your process, then you won’t yet have time to measure how that work is flowing. Similarly, if you suddenly remove a lot of work in the middle somewhere, the math is going to break.

4. Average Age of WIP is Relatively Constant

You can measure WIP age if you measure how “old” your WIP is (the difference between today and the day the work entered the system or state). It’s a good idea to produce an aging histogram to analyze your WIP average age. If this is too variable, the math for Little’s Law breaks. Again this makes sense since items that age too long are not flowing well and items that age too quickly probably indicate an issue with measurements.

Then What’s the Use of Little’s Law?

As Vacanti points out, the assumptions of Little’s Law are actually more important than the math itself. What you should be doing with Little’s Law is constantly evaluating how well you’re tracking to the assumptions. If any of the metrics start skewing (like average age of WIP is all over the place) then you have a good leading indicator that is pointing to process issues.

Context is important - even if you’re presented with a CFD that looks textbook with nice, even bands - that doesn’t mean that your process is perfect. You still need to interpret the data and charts in context of what is happening with the team that is being measured.

Forecasting with Little’s Law

Vacanti points out that it’s a mistake to forecast solely based on the math of Little’s Law. The main reason is that you cannot assume that nothing will change in the future. Little’s Law works on historical data, but since it depends on these assumptions, you cannot use it to forecast. At best you can use it to “gut check” when you’re doing any sort of forecasting. That’s a topic for a different post.

Variability

I made mention earlier that too much variability in WIP age can be bad. So does that mean that you have to estimate all your work items to be a constant effort or number of story points?

No! One beauty of Little’s Law is that it works without having to know the size or complexity of the items in the system. However, since the law works on averages, too much variation in the averages is bad. Remember the assumptions revolve around the overall stability of the system - if the underlying system itself is fairly stable, then it can absorb variation and is predictable. However, if the underlying system is constantly changing, then predictability is a pipe dream.

Conclusion

Little’s Law isn’t a lie - as long as you’re adhering to the assumptions that need to be met in order for it to work. Teams that pay attention to the assumptions and address behaviors, patterns or practices that break the assumptions are far more likely to gain process efficiency. As teams improve the stability of their systems, they become more predictable and that’s good for the team as well as for the end users the team is trying to serve.